A skipjack tuna caught off the Copper River in Alaska. There had been one confirmed documentation of such a fish in Alaska in the 1980s. (Courtesy of Alaska Department of Fish and Game.)

Something odd is happening in Northern Pacific waters: They’re heating up. In fact, it hasn’t been this warm in parts of the Gulf of Alaska for this long since researchers began tracking surface water temperatures in the 1980s, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

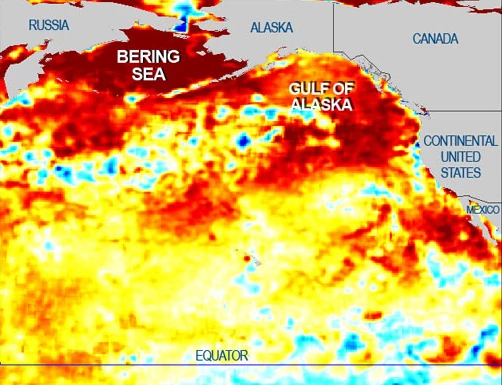

The warming began last year in the Gulf of Alaska and has since beendubbed “The Blob” by Nick Bond, of the Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean. Temperatures have been as high as about 5 degrees Fahrenheit (3 Celsius) above average.

Normally storms and winds roll through to cool off the surface of the Northern Pacific, but a weather pattern popped up for a few months in winter 2013 that inhibited those storms from developing, said Nate Mantua, a NOAA research scientist. Then, from October 2013 through January, the weather pattern came back as a ridge of high pressure (the same one connected to the California drought). All of that made the already warm waters in the Alaskan gulf even warmer, a layer about 100 meters thick, Mantua said.

In the spring, warm water started to develop in other Northern Pacific waters, namely the Bering Sea. There’s also a chunk of warm water developing off the coast of California.

“You have lots of warm water, and it’s due to weather patterns that basically don’t take heat out of the ocean,” Mantua said. “They are letting the ocean warm up rapidly, and stay warm.”

The change in surface water temperature doesn’t appear to be a manifestation of global warming, but rather the result of weather and wind patterns that change quickly and vary year to year, Mantua said.

Take a look at this map of surface water temperatures. The deeper the red, the higher the above the average temperature:

And now, strange fish are showing up. In the past year, there have been “unusual fish occurrences” in Alaskan waters, according to NOAA research biologist Joe Orsi, such as the skipjack tuna in the photo above. The last documented skipjack tuna in Alaska was in the 1980s.

In August, a thresher shark was caught in the Gulf of Alaska, Orsi noted. Those sharks are more typical off the coasts of British Columbia and Baja California. Two other threshers were spotted in the past four years in the more southern waters of the Alaskan gulf.

An ocean sunfish, the world’s largest bony fish, has been spotted on the surface of the Prince William Sound off Alaskan shores, Orsi said. Further south, a 7-foot-long ocean sunfish washed up on the shore in Washington state in August.

In this Aug. 29 photo, a 7-foot ocean sunfish rarely seen in Washington waters washed ashore on a beach near Ilwaco, Wash., with June Mohler, a biological technician working as an interpretative assistant. (AP Photo/Cape Disappointment State Park, Eric Wall)

The warm water could throw the food chain into a bit of disarray. Just as warmer water fish have been showing up, salmon could be finding less of the high-fat food they need to chow down on. That’s important because the Northern Pacific is considered a “fish basket,” and most American salmon comes from the Alaskan gulf.

“The fish migrated out of rivers in June, got to the gulf by August, and they will have arrived expecting to find cold water and abundant feed,” said Bill Peterson, a senior scientist with NOAA fisheries. “They’re going to find nothing to eat, is what we suspect…. It won’t be pretty.”

It’s possible that the fish could dive down deeper and feed in the colder waters below the surface, Peterson said. Either way, fisheries won’t feel the impact until the salmon return in another two to three years.

Around 2005, when similar warming occurred in Northern Pacific waters, particularly in Northern California, “Pacific salmon died in extremely high numbers,” Mantua said. “Fisheries, three years later, curtailed or even shut down in California for the first time ever.”

But it’s still an open question as to how these warmer waters will affect salmon populations. Mantua isn’t convinced that “The Blob” means loads of dead fish. He points to past warm years that resulted in high salmon returns. “It’s unsettled whether this is bad news” for salmon, he said. “We have to wait until the adults come back, and we’ll have to see.”

Please click here to see why they are catching yellowfin tuna and wahoo offshore of southern California and skipjack tuna offshore of Alaska this September (HINT: WARM water this year!!!) – this is a graphic courtesy of NOAA/ESRL showing the weekly SST anomalies for the past 52 weeks.

The above article is re-posted from washingtonpost.com – please click here for the original article.