Originally Published: March 2023 | earthobservatory.nasa.gov | Please click here for original article.

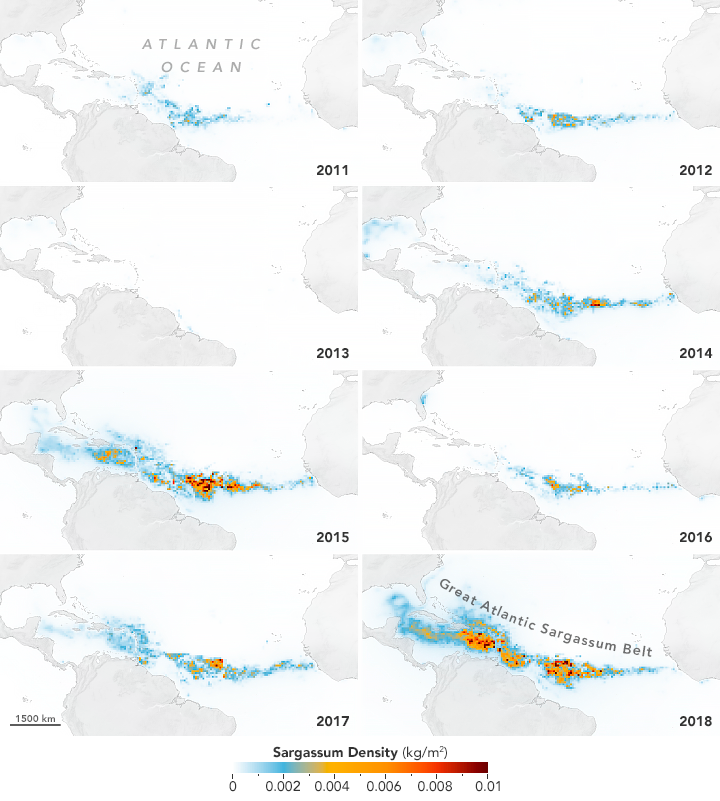

Above: 2013

Nearly every spring and summer since 2011, a giant bloom of seaweed has developed in the central Atlantic Ocean. Patches of floating brown seaweed—known as Sargassum—have stretched from the west coast of Africa to the Gulf of Mexico in what is known as the “Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt.” In March 2023, scientists found that the amount of Sargassum floating in the belt was the largest of any March on record.

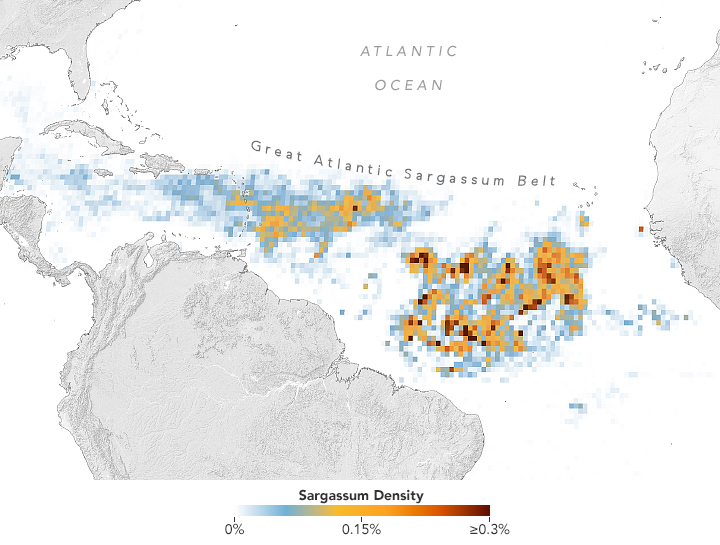

The map above shows Sargassum density in the central Atlantic Ocean (including the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico) for March 2023. Red and orange areas show where Sargassum densities were the highest, in terms of the percent of the pixel covered with the seaweed. The data for the map were developed by scientists at the University of South Florida (USF) College of Marine Science using data from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instruments on NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites.

USF researchers estimate that the Sargassum belt in March totaled about 13 million tons, a record amount for this time of year. “So far this year, record high Sargassum abundance is mostly in the central East Atlantic,” said Brian Barnes, a marine scientist at the Optical Oceanography Laboratory at USF. “But in other parts of the Atlantic and Caribbean, its abundance is still high—in the 75th percentile of measurements made between 2011 and 2022.”

In patchy doses in the open ocean, Sargassum contributes to ocean health by providing habitat for turtles, invertebrates, fish, and birds and by producing oxygen via photosynthesis. But too much of this seaweed near the coast can make it difficult for certain marine species to move and breathe. When Sargassum sinks to the ocean bottom in large quantities, it can smother corals and seagrasses. On the beach, rotten Sargassum releases hydrogen sulfide gas and smells like rotten eggs. This has the potential to cause major issues for both marine ecology and local tourism.

Since its development in 2011, the Atlantic Sargassum belt seems to be getting larger, according to Barnes and his colleagues. The maps above show the monthly mean density of Sargassum in the Atlantic Ocean in each July from 2011 to 2018. The summer of 2018 saw a record abundance of 20 million tons in July, which wreaked havoc on shorelines in the tropical Atlantic.

Although the cause of this growth is not immediately clear, the researchers found in past research that nutrient inputs from fertilizers and other sources are correlated with larger blooms. Changing ocean circulation patterns are also a factor because Sargassum grows faster when sea surface temperatures are normal or cooler than average.

Sargassum density typically peaks in June or July, still a few months away, but there were already signs in March that the bloom in 2023 could be the largest ever recorded. “Major beaching events are inevitable around the Caribbean and along the east coast of Florida as the belt continues to move westward,” Barnes said. However, the exact timings and locations of these landings are difficult to predict. Clusters of some of this year’s Sargassum already landed in southern Florida, on beaches in Key West, Miami, and Fort Lauderdale.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin and Joshua Stevens, using MODIS data courtesy of Brian Barnes at the University of South Florida (USF), Optical Oceanography Lab and Wang, M., et al. (2019). Story by Emily Cassidy.