Article By: Tony Bartelme | Originally posted: September 5, 2018 | Please click here for original article.

Off South Carolina, the ocean suddenly changes color, from green to deep blue. You’re in the Gulf Stream now, in warm and salty water from the tropics, with swordfish, tuna and squid, in a current so strong that it lowers our sea level.

Benjamin Franklin would learn about this current’s force. He was a Colonial postmaster before the American Revolution, and he’d noticed British mail ships were slow, much slower than other merchant ships. Why?

He mentioned this to his cousin, Timothy Folger, a ship captain who’d hunted whales off New England. Ah, yes, that current off the East Coast, Folger told Franklin. Any fishermen worth their nets cut in and out to make better time — the whalers had even warned the mail ships to steer clear. But the Brits “were too wise to be counseled by American fishermen.”

A map might help, and so they made a chart of this “Gulf Stream” from Florida toward Europe. It was one of the first maps to document its tremendous reach.

Map or no map, the British mail ships still bucked the current, and letters still arrived more slowly than they should have. But there it was now, on paper, a massive river in the sea, a swift flow with mysteries scientists have only begun to solve.

The Gulf Stream is one of the mightiest currents on Earth. It moves at a rate of 30 billion gallons per second, more than all of the world’s freshwater rivers combined. On its way, it hauls vast amounts of heat; a hurricane that twists into it gets a blast of fuel. It’s a highway for migrating fish and a destination for deep-sea fishermen. It courses through an area that oil companies want to probe; an oil spill in the Gulf Stream would spread far and wide.

Though just 50 miles from Charleston, the Gulf Stream has so much momentum it tilts the sea level down like a seesaw. If you could walk on water, a trek from the Gulf Stream to Folly Beach would go downhill 3 to 5 feet. Put another way, without the Gulf Stream whisking all that water past us, our tides would be at least 3 feet higher.

In 2009, the Atlantic’s system of currents, including the Gulf Stream, slowed by 30 percent in a matter of weeks. Sea levels in New England also rose 5 inches above normal. Scientists were stunned. The currents regained their strength a year later, but scientists wondered: Was this a blip? Has global warming somehow gummed up the currents? If so, what’s next?

The race to understand the Gulf Stream and its associated currents is a deep dive into history, technology and recent aha moments in science.

It involves messages in bottles, abandoned telephone cables and undersea waterfalls.

The story has largely been missed amid the ebb and flow of other climate issues.

But the impact of this great current is undeniable. Changes in its velocity could rearrange marine life throughout the hemisphere. If it’s slowing for the long term — as a growing chorus of scientists fear — sea levels on the East Coast would rise more quickly, further threatening billions of dollars in shoreside property. It would alter weather patterns, affecting everything from hurricanes here to monsoons in India.

Beyond these stakes, this race also is about something else: the human drive to explore, that irresistible itch to look beyond what we know.

It could begin with Franklin’s epiphany about the slow mail.

But why not start with Ringo?

CHAPTER 2: A mission to drift

“We all live in a yellow submarine, yellow submarine, yellow submarine … ”

It was summer, 1969, a time of inner and outer exploration, Woodstock and an Apollo moonshot. The Beatles’ “Yellow Submarine” movie was out, with Ringo Starr doing lead vocals on its title song. Capt. Don Kazimir picked up a cassette at a West Palm Beach mall. Catchy song. Perfect, really, given that he would soon pilot a real (partly) yellow submarine.

Kazimir was in his mid-30s, compact and wiry, with dark-rimmed glasses, more serious than swashbuckling, but his fascination with the sea ran deep. He was born in Ossining, N.Y., where his father worked at Sing Sing, the old prison on the murky Hudson River.

Kazimir had always loved trips to beaches on Long Island. But, in fifth grade, his mother bought him Jules Verne’s “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea,” and his compass was set. Captain Nemo’s tortured adventures? A battle with a giant squid?

Hooked, he later joined the Navy, became an officer and went to sub school in Connecticut. He played cat-and-mouse with Soviet submarines off Finland. He hoped someday to command his own ship, came close a few times, but Navy life is hard on families. So he retired before reaching that goal and took a job with Grumman Aerospace Corp. Then, one day while paging through Popular Science magazine, his eyes landed on a story about the Gulf Stream Drift Mission.

The mission was Jacques Piccard’s idea. Piccard was a famous Swiss explorer who, along with a Navy diver, had ridden a submersible 35,800 feet down into the Pacific Ocean’s Mariana Trench, deeper than anyone else. Now Piccard had his sights on the Gulf Stream — a different challenge. No sea trench to reach; no immovable object to conquer. The Gulf Stream was a destination that moved. To truly explore it, you had to become part of it.

Piccard had somehow persuaded Grumman to build a submarine without any serious means of locomotion. It had four 25-horsepower motors, enough for minor maneuvers but too puny to move the sub’s 140 tons out of trouble. It was 50 feet long and had 29 portholes. It was painted yellow on top to make it more visible to surface ships, white on its underbelly. With its viewports and yellow-and-white paint scheme, it looked like a tube of Swiss cheese.

NASA signed on because the six-person crew would be sealed inside for a month, an experiment that would mimic living in space for an extended time. The Navy joined because observations might yield helpful data for submarine warfare. Piccard had noted: “If we are able to drift silently all along the American coast, several other submarines, maybe not American, will be able to do it, too.”

Piccard needed a captain. Kazimir applied and finally won his first command.

The group christened their submarine the Ben Franklin because of his pioneering chart. And on July 14, 1969, a Navy ship towed the sub 19 miles off Palm Beach, Fla.

“Open the vents,” Kazimir ordered. Water filled the ballast tanks.

Soon, the yellow submarine was under the waves, drifting.

[responsive] [/responsive]

[/responsive]

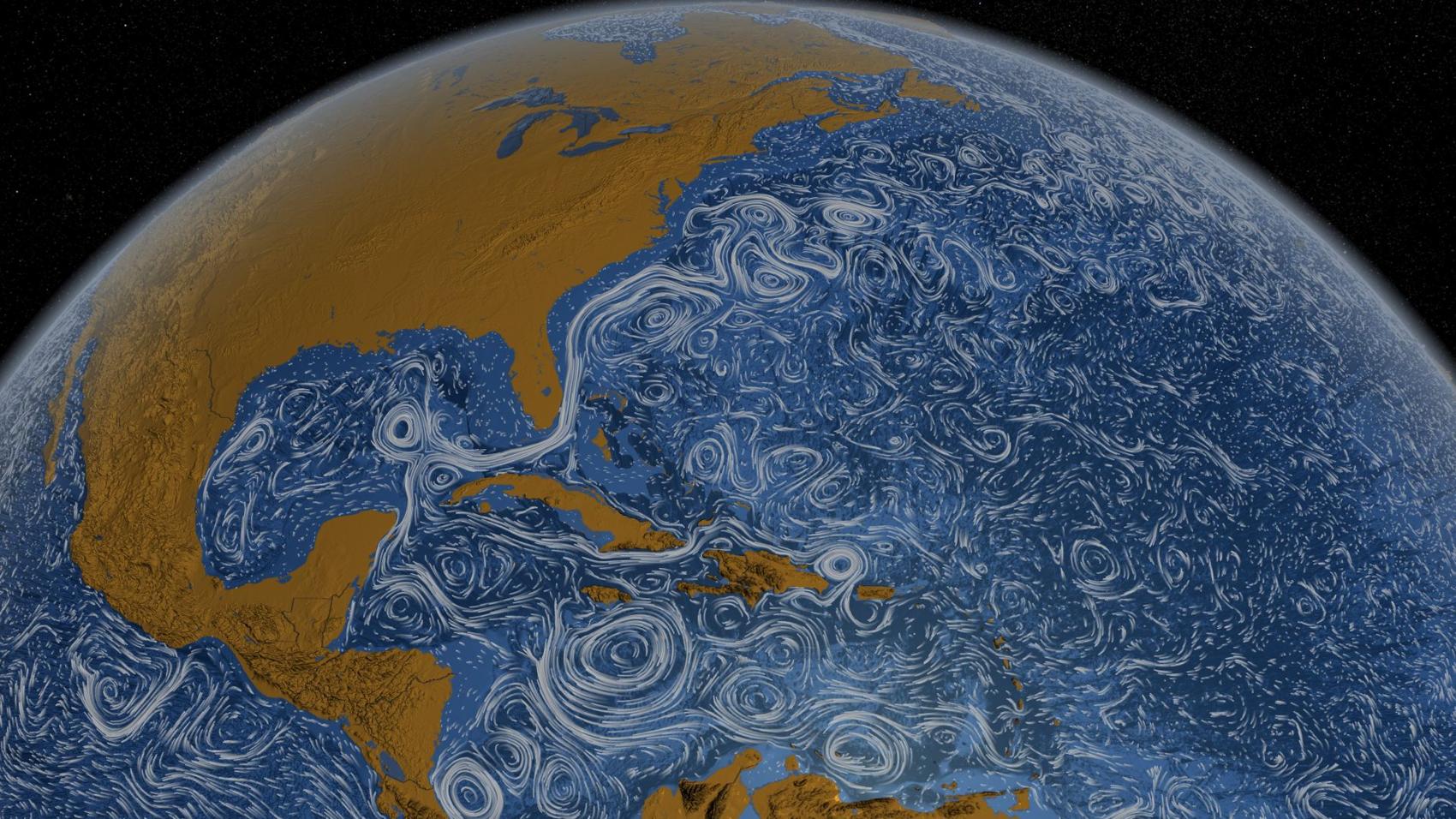

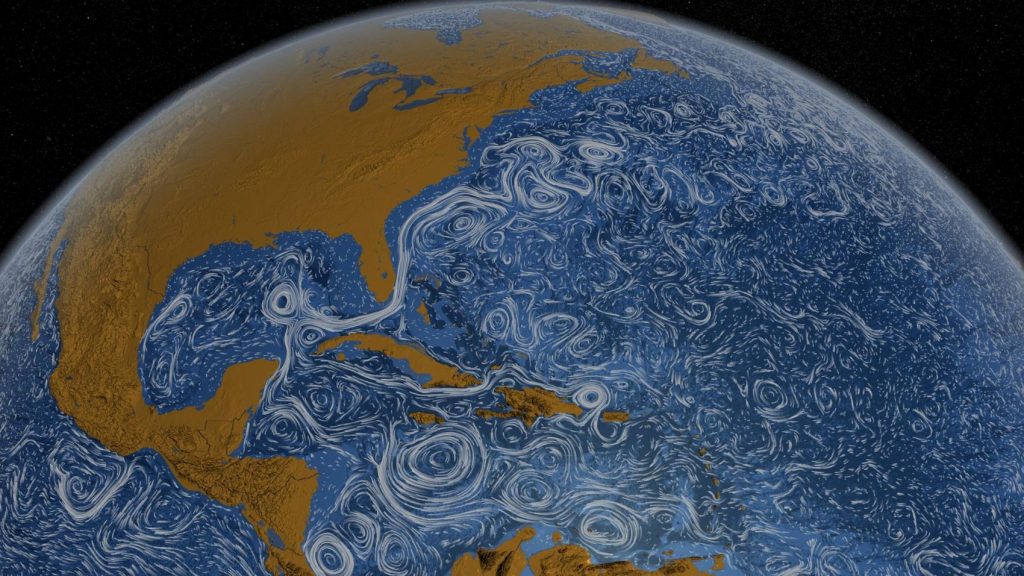

Above: Currents in the Gulf of Mexico join ones from the Caribbean near Florida to create the Gulf Stream. NASA created this visualization from satellite data. Courtesy:

CHAPTER 3: The great conveyor belt

The mission launched in what’s generally considered the beginning of the Gulf Stream, the straits between the Bahamas and South Florida.

Here, currents from the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean tropics converge, forming a single hot flow.

Pushed by trade winds, the Gulf Stream rolls north along the Florida coast.

Sixty miles wide, it gathers force as it passes Georgia and the Carolinas, its flow 6,000 times greater than the Mississippi River.

Past South Carolina, the Gulf Stream nearly collides with the Outer Banks, missing Cape Hatteras by just 12 miles. Then it jets northeast, surging deeper into the Atlantic.

Away from land now, it undulates like a dropped fire hose. It spins off eddies that swirl in great arcs. Like long curls, the current and its eddies flow across the Atlantic toward northern Europe. Along the way, these curls carry heat equivalent to a million nuclear power plants.

On its journey, the Gulf Stream can be 15 to 20 degrees warmer than water outside it. During winter, steam wafts off it like smoke. During spring and summer, its heat rises and boils into massive thunderheads. One year, scientists noticed a 600-mile-long line of clouds over it, as if a jet had created an immense contrail.

In the North Atlantic, winds blow over the Gulf Stream and warm Iceland like a radiator. Farther south, it fuels tropical storms.

In 1989, Hurricane Hugo crossed the Gulf Stream and hit the warmest water since the Caribbean. The stream gave the storm “a sudden shot of high octane,” a meteorologist said at the time. Charleston wouldn’t be the same for years.

When winds turn against the Gulf Stream, steep waves form, giant castles of water and foam. In 2005, a 70-foot wave struck the Norwegian Dawn cruise liner as it steamed from the Bahamas to New York for a product-placement appearance on NBC’s “The Apprentice.” Waves broke over the bow, flooded 60 cabins and tossed debris as high as the ship’s 10th deck. It limped into Charleston for repairs.

When caught in the Gulf Stream’s flow, stuff and people go far. Between 2000 and 2007, researchers tossed 1,200 bottles off the Canadian coast, each with a message to report its location if found. The bottles landed on beaches from Finland to France.

In 1986, Nelson McIntosh lost power on his boat between the Bahamas and Florida. He drifted in and out of the Gulf Stream for about 50 days and more than 400 miles, surviving on rainwater collected in his seat cushion. When fishermen rescued him off Charleston, he’d lost 80 pounds. His first request was a beer.

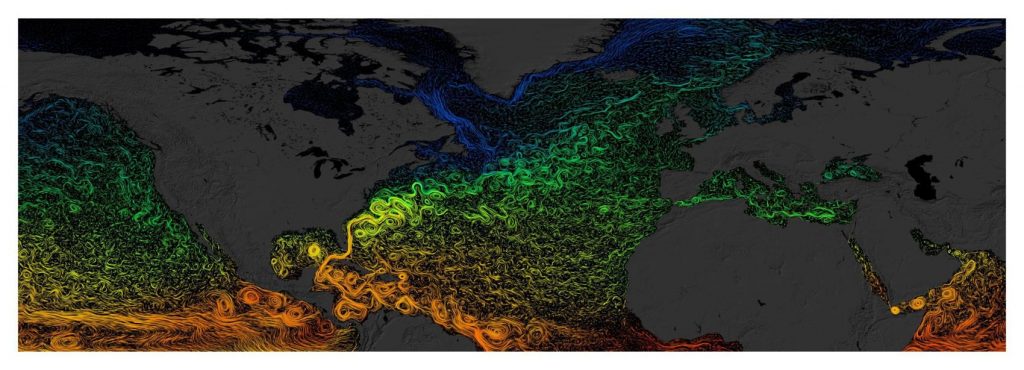

Though it has a name, the Gulf Stream doesn’t really have a true beginning or end. That’s because it’s part of a larger and mostly hidden conveyor belt of currents, a system that keeps the planet’s climate in check.

And on this belt in 1969, the six crew members of the Ben Franklin floated north, picking up speed.

CHAPTER 4: Bump in the road

They spent hours gazing through the portholes. Off Cape Canaveral, they saw things out of Captain Nemo’s logs: a squid attached to one of the viewports and a large colony of medusa jellyfish, their long tentacles wrapping around each other in a graceful embrace.

At night, the sub’s lights lured plankton and other tiny organisms. Flashing glints of blue, yellow and orange, they swirled like turns of a kaleidoscope. Because it seemed to fit the mood, Kazimir played the opera “Madame Butterfly” on his cassette deck, especially when the salps floated by — translucent sacs that expanded and contracted like lungs, then joined in long chains and twirled as if in a dance.

The sub seemed to become one with the Darwinian world around it, both predator and prey. As Frank Busby, a Navy oceanographer, looked out a porthole, a large swordfish attacked, ramming the sub just below the window, damaging neither sub nor fish. Squids squirted dark ink and bolted. Cuttlefish launched clouds of sepia. Drifting with the ink clouds, the crew watched them expand slowly like Rorschach tests.

Diving now, down 2,000 feet to the seabed, another world appeared: skeletal crabs poking along a sandy bed, even a small ray.

Despite the crushing water pressure, there’s still so much life down here, Kazimir thought.

Another thought, a fear, sometimes washed through his mind: Is the sub going to make it with all those portholes? At such depths, one bad weld or a crack could send water shooting in like a laser. The sub would implode in an instant.

Off Georgia, the sub began to rise and descend on its own, up and down 200 feet in 30 minutes. They couldn’t feel this motion because they were part of it, just as a passenger in a hot-air balloon feels no breeze. But they saw what was happening on their instruments: They were in the Gulf Stream’s internal waves, great deep-water rollers that rise and fall like slow-motion breaths.

Tensions rose. The internal waves “are giving us fits,” Kazimir wrote in his log. Temperatures inside the sub dropped to 53 degrees. Kazimir doled out a few mini-bottles of whisky and Scotch to warm bodies and spirits, a Navy tradition. They paid close attention to sonar readings. Uncharted shipwrecks could be disastrous, and they were near the last-known coordinates of a missing World War II tanker.

In 1943, a German U-boat fired torpedoes at the Esso Gettysburg. Bursting into flames, it sank with 131,000 barrels of oil. Years later, with the shipwreck still not found, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration would estimate that if 10 percent of this oil leaked into the Gulf Stream, the slick could affect an area the size of California.

Suddenly, off Georgia, the sonar picked up something ahead. Kazimir raised the sub from a depth of 750 feet to 100. It wasn’t a shipwreck. It was much larger. A coral reef? Nothing on the charts.

The seabed was more complex now, a series of undulating scarps and caves. Hiding in the caves were great schools of wreckfish and squid. Those squid were “more beautiful than anything we had seen previously,” the crew reported to the surface ship tracking them.

Some features rose 400 feet, and oceanographers would later name this rugged area the “Charleston Bump.” It deflects the Gulf Stream like a rock in a river rapid, creating eddies and turbulence.

On Day 11, the Ben Franklin found itself in one of those eddies circling back toward the South Carolina coast.

Kazimir cranked the sub’s tiny motors to move back into the current. Nothing doing.

Piccard wrote: “The Gulf Stream has rejected us.”

CHAPTER 5: A wrench in the machinery

Science is like a great current, a flow of ideas and surprises. It was especially so in 2009, when researchers watched in awe as the Atlantic’s conveyor belt suddenly slowed as if something was caught in its gears.

Some had feared this might happen. Carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere had spiked — from 310 parts per million in 1960 to roughly 400 parts per million. The Earth’s oceans and atmosphere also had warmed rapidly, causing Greenland’s glaciers to melt at rates unseen in hundreds of years. Roughly 269 billion tons of Greenland ice melt every year. This massive infusion of freshwater poured into areas near a critical point in that conveyor belt — the place where the Gulf Stream takes a deep dive.

Between Greenland and Norway, the Gulf Stream’s warm and salty flow cools, which makes it dense and heavy. This heavier water then drops like a slow-moving waterfall. It sinks to the ocean floor, where it joins currents moving south. Scientists call this system the “AMOC,” short for Atlantic meridional overturning circulation.

A crimp in the conveyor belt would vibrate across the globe. With slower currents moving south, hotter places would get hotter. With less heat going north, winters in Europe would get colder. A sluggish AMOC could change monsoon cycles in Asia and South America. It would give tropical storms in the Caribbean more time to form and linger. This would lead to more downpours and stronger hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico and Southeast. The sea level would rise along the East Coast.

But until 2004, scientists had just a few ways to measure this conveyor system. One was an abandoned telephone cable strung between Florida and the Bahamas. Through a nifty bit of physics, oceanographers figured out how to calculate the Gulf Stream’s velocity by analyzing the line’s voltage. But it was just a snapshot of one part of the conveyor belt, so scientists in the early 2000s launched RAPID-AMOC, an ambitious international program to string monitoring stations across the Atlantic.

And in 2009, these stations recorded a sudden 30 percent drop in the AMOC’s flow.

“It was totally unexpected,” said Harry L. Bryden, an oceanographer in England who’d organized the monitoring effort there.

“It was like nothing we’d seen before,” said William E. Johns, an oceanographer in Miami who’d led from the American side.

As the flow diminished, weird things happened: Europe had record-breaking snowfalls; sea levels north of New York City rose 5 inches; the Gulf Stream twisted farther north; temperatures in the Gulf of Maine shot up faster than 99 percent of the world’s oceans; codfish stocks there plummeted; Norfolk, Va.,’s low-lying streets flooded more frequently on sunny days; Charleston’s tides were higher than predicted.

A huge change in the world’s underwater machinery was underway, hidden below the waves.

CHAPTER 6: Living in a greenhouse

Rejected from the Gulf Stream, Kazimir brought the sub to the surface, moving through brighter shades of green. In the sunlight, they saw diatoms, tiny plants that soak up carbon dioxide and rival snowflakes for their beauty and sparkle. They saw barracudas and hammerhead sharks.

They broke through the waves but kept the hatch sealed, kept their micro-climate intact to preserve NASA’s research.

They’d already learned that six guys in a tube gets noisy, making sleep difficult at times. And Piccard wasn’t impressed with the food: canned, freeze-dried and packaged stuff. Kazimir didn’t mind. He was used to worse on Navy subs. But everyone agreed: Bringing that dartboard was a great move. NASA later made sure one went up with the space station Skylab, though with tips made of something new called Velcro.

The sub’s climate grew dirtier as time passed. The waste system struggled. The air stank. Two crew members developed a rash.

“Probably due to perspiration and the fact that underwear was changed every 3 days (not often enough),” Kazimir wrote in his log.

To keep the sub from turning into a greenhouse, they deployed rolls of silica gel to sop up the humidity. They hung them everywhere like deli sausages. They had plenty of oxygen; it came from liquid oxygen tanks. But CO2 levels rose quickly. They monitored themselves for headaches, fatigue and the shakes — signs of CO2 poisoning. Panels of lithium hydroxide captured excess CO2. When the crew changed them, powder filled the cabin and made everyone cough.

Drifting on the surface, the crew listened to CBS News Radio 88. The Apollo mission to the moon had just happened. One small step on the moon, a small step backward out of the Gulf Stream.

A Navy ship pulled aside and attached lines. The tow back into the Gulf Stream took seven hours, from green water to blue.

Released from the lines, the sub went back under.

Kazimir inserted a cassette: Willie Nelson. They were on the road again.

CHAPTER 7: New explorations, new discoveries

Science also is like the turbulent current Kazimir and his crewmates were in off Charleston, with eddies of confusion and debate amid a stronger forward flow.

In 2010, the Atlantic conveyor belt regained its strength — almost. Its velocity was still weaker than before.

Scientists paddled harder to find out what happened and what it meant.

They studied tidal gauges, wind patterns and data from that abandoned telephone line, the one strung between Florida and the Bahamas.

William Sweet, a NOAA oceanographer in Maryland, discovered that the slowdown came amid other changes in the weather. The combination generated higher tides from Georgia and Virginia, tides that pushed water into normally dry streets.

“People can literally put their feet in the water and say it’s related to the Gulf Stream offshore.”

Tal Ezer, a scientist at Old Dominion University, uncovered evidence that hurricanes off Florida could disrupt the Gulf Stream for several days, triggering sunny-day floods hundreds of miles away in Norfolk, where the school is located.

Could a force as powerful as the Gulf Stream be so fickle?

Tom Rossby, a Rhode Island oceanographer, was skeptical. He’d set up a program to measure the Gulf Stream by outfitting a freighter with instruments. The freighter had made regular runs between New Jersey and Bermuda for more than 20 years.

“I can happily report that the Gulf Stream isn’t slowing down,” he would say. His direct measurements were proof. “It’s really quite stable. Papers that say otherwise are baloney.”

Over the next few years, the flow of papers increased. Teams of researchers looked for clues in cores and fossils; they gathered data from new monitoring stations in the North Atlantic — the place where the Gulf Stream does its deep dive. They ran programs on computers capable of doing quadrillions of math problems a second. Stable? The Gulf Stream?

Not if you looked at the entire conveyor belt, scientists including Harry L. Bryden countered.

Then, in April 2018, Nature, the science journal, published two alarming studies.

Chapter 8: Getting clearer

Each study was based on years of research. One team used sediment cores from the ocean floor along the East Coast. The cores told you things about ocean temperatures in the past, just as the width of tree rings tell you when growing seasons long ago were good or bad.

The study found the Atlantic’s conveyor belt began to slow in about 1850, weakening as the Little Ice Age ended. Researchers said that rapidly rising greenhouse gases may have amplified this natural weakening trend.

A second team analyzed sea temperature records and ran simulations on a super computer. For climate scientists, these computer models were like new high-definition TVs. Once-fuzzy images of the Atlantic’s conveyor system suddenly grew clearer.

They found that amid a rapid increase of carbon dioxide levels, the Atlantic’s current system had weakened since the 1950s. The reduced flow was equivalent to roughly 14 Amazon Rivers. Researchers said a slower flow could have shifted the Gulf Stream farther north, created more storms in Europe and worsened droughts in parts of Africa.

The studies had different methods but similar conclusions: the Atlantic Ocean conveyor belt had slowed by 15 percent.

By some measures, it was at its weakest point in 1,600 years.

CHAPTER 9: Surface

Past Cape Hatteras, the Ben Franklin entered deep water, drifting with schools of migrating tuna.

Past Virginia, then Maryland, and the Ben Franklin picked up speed, moving at 5 mph.

Past New Jersey and Massachusetts, and Don Kazimir wrote in his log, “the crew is getting restless.”

Inside, carbon dioxide levels reached more than 13,000 parts per million. Crew members reported feeling short of breath at times. But the mission was nearing its end. Frank Busby, the Navy oceanographer and a heavy smoker, was desperate for a cigarette. To Kazimir, it seemed as if he’d had his bags packed for days.

On Day 30, Kazimir prepared to surface off Nova Scotia. They took last looks through the viewports as the sub rose in the brightening light: A jellyfish floated by; a chain of salps did their dance. By then, Chet May, a NASA engineer, had inserted that Beatles cassette for the last time.

“And we lived beneath the waves in our yellow submarine.”

By all accounts, the Ben Franklin mission was a success. The Gulf Stream had never been analyzed so deeply. Crew members made 900,000 measurements of temperature, salinity and other features. They’d been surprised by the size and power of those internal waves, the turbulence off Charleston, the attacks by those foolhardy swordfish. They’d withstood 30 days in an unheated metal tube, a record for a civilian sub.

But the mission was largely lost to history. While the aquanauts of the Ben Franklin were under the waves, the Apollo astronauts walked on the moon. The world was looking up, not down, and after some time, the Ben Franklin ended up in a Canadian junkyard.

More years would pass before a maritime museum in Vancouver, British Columbia, discovered this bit of history hiding in plain sight. The museum restored the Ben Franklin and put it on display, touting “The Story of Our Yellow Submarine.”

Today, Don Kazimir, at 84, talks about the Ben Franklin expedition with the kind of urgency you hear near the end of long missions. He’s one of two surviving crew members, recently retired from a Catholic charity, living near the water in South Florida on Gulfstream Road.

One recent afternoon, he pulled out boxes he’d stowed in a closet and his garage: Ben Franklin mission patches, his uniform, log books, charts. Memories resurfaced about those glittering plankton and ink-squirting squid. He found himself thinking hard about the mission’s legacy, his place in it, Greenland’s melting ice, the impacts of a slowing Gulf Stream — the importance of exploring all parts of Earth, a blue-and-green submarine drifting in space.

“That’s the curiosity built in all of us, to learn.”

Meanwhile, across a lagoon by Kazimir’s house, the Atlantic lapped onto an eroding beach. And, beyond the horizon, the blue Gulf Stream flowed, its power and changes hidden a little less now because of explorers in science and a yellow submarine.

[responsive] [/responsive]

[/responsive]

Above: The Gulf Stream is part of a complex system of ocean currents that keep the planet’s climate in check. NASA/Provided: