Article Courtesy: Earth & Space Science News by: JoAnna Wendel | Originally Published: June 18, 2015 | Please click here for original article.

An ensemble of four computer models evaluated river runoff, wind patterns, and other factors affecting the extent of oxygen-poor waters near the Mississippi River’s mouth.

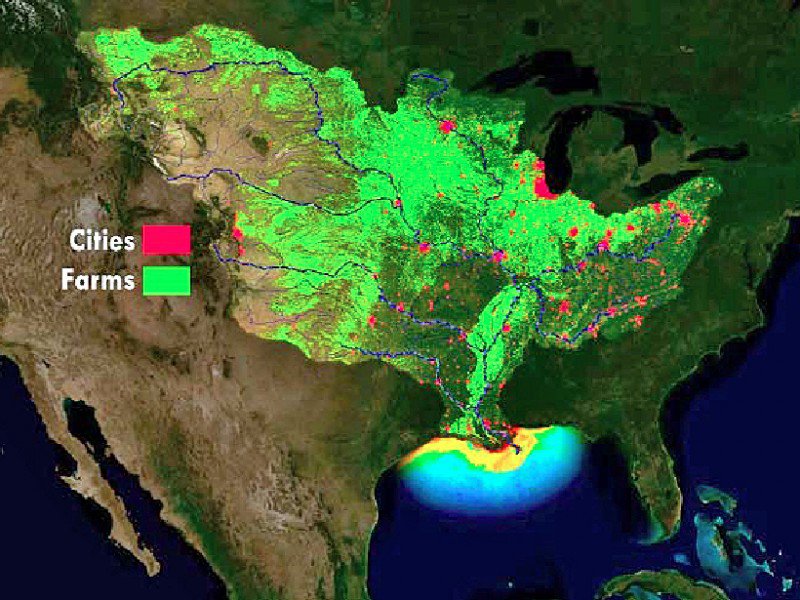

Above: A visualization of how nutrient runoff from farms (green) and cities (red) in the Mississippi River Basin influences algal blooms in the Gulf of Mexico. The warmer colors represent a higher concentration of algae. NOAA scientists predict that the size of the 2015 Gulf of Mexico dead zone, which is caused by the decomposition of these blooms, will be about the size of Connecticut. Credit: NOAA

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) released on Wednesday its prediction of the size of the annual Gulf of Mexico dead zone, which the agency forecasts to span about 14,200 square kilometers—about the area of the state of Connecticut. The actual size of this summer’s dead zone will be studied and announced in early August.

This huge expanse of oxygen-depleted Gulf waters just beyond the Mississippi River Delta forms every summer after nutrients from wastewater and vast amounts of fertilizer used by farmers wash down the river and run off the Louisiana and Texas coasts during the rainy spring. The extra nutrients—mainly chemical compounds containing nitrogen or phosphorous—nourish huge blooms of algae.

When the algal blooms eventually die, they fall to the sea bottom and decompose, soaking up the available dissolved oxygen. As oxygen levels fall too low to sustain most marine life, bottom-dwelling animals like crabs and shrimp cannot thrive and often flee the area, which can devastate the Gulf’s seafood industry. Other, less mobile species may not survive.

“What we’re trying to do is better understand the variability in size [of the dead zone] from year to year so we can better inform fisheries and management along the Gulf Coast” about where and when to expect potential shortages in their catch, said Dan Obenour, an environmental engineer at North Carolina State University, Raleigh.

Modeling the Dead Zone

This year, the U.S. Geological Survey estimated that 104,000 metric tons of nitrate and 19,300 metric tons of phosphorous have already flowed into the Gulf of Mexico in May alone. To predict the dead zone’s expected size, NOAA combined results from four different computer models that weigh factors such as nutrient runoff, wind velocity, and other weather conditions. This is the first year that multiple models are being used. The predicted 2015 dead zone is about the average size the zone has been for the last several years.

One of the models, developed by Obenour and his colleagues, includes measurements of wind velocity over the continental shelf off Louisiana and Texas, where the dead zone occurs. Wind can affect the size of the nutrient load delivered to the shelf, fueling the formation of the dead zone, Obenour said.

Wind can also affect the amount of fresh water that flows into the shelf region, which causes the water column to separate into a colder, denser, saltier layer beneath a warmer, more buoyant, fresher layer. This stratification exacerbates the dead zone by preventing mixing of the layers, which would otherwise inject oxygen into the bottom layer.

Last year, a team of researchers analyzing a global database of more than 400 dead zones, including the one in the Gulf of Mexico, found that many of them could experience a sea surface temperature rise by the end of this century that could worsen stratification, increasing the size of dead zones.