Article By | Terry Gibson* | February 25, 2015

Any good fisherman knows that if you find the bait, you’ll find the fish. This quest has pushed oceanographer Mitchell A. Roffer, Ph.D., to improve our understanding of what drives fish migrations and how to better forecast when and where anglers can target their favorite species.

Roffer, an adjunct professor at the Florida Institute of Technology, created Roffer’s Ocean Fishing Forecasting Service Inc. (ROFFS™), a state-of-the-art system that analyzes ocean circulation and provides fishermen with data and forecasts indicating where to find fish. The company’s services also are employed by several state and federal agencies, including NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. These agencies use ROFFS™ to track dispersal of pollution, including from the Deepwater Horizon disaster and from the phosphate mines at Piney Point, Florida, among other sources, and help understand changes in fish distribution and catch, among other things.

Roffer, an accomplished offshore angler, inshore kayaker, and diver, has become an important liaison between the scientific community and fishermen. He recently spoke with The Pew Charitable Trusts’ recreational fishing outreach consultant, Terry Gibson, about how changing oceanographic conditions influence the location and abundance of baitfish, also known as forage fish. Roffer explains the role that these fish play in ecosystems and the need for policies that protect enough forage species to serve as prey for marine animals and popular-to-catch fish.

Gibson: Mitchell, how did you become interested in fish and fishing?

Roffer: In graduate school, I chose to study environmental protection and fisheries. I earned an internship working for NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service while at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, and in 1976 we competed and won a grant to study bluefin and other species using satellites and catch data. Those years were really special. I spent so much time offshore with really experienced honest fishermen. I learned to deeply respect their knowledge and really appreciate their help. I remain in contact with many of them today.

When did you conceive of ROFFS™?

While working at the University of Miami, I had boat captains asking me to help them find fish. I felt obligated since they let me on their charter boats every day for three years to do my Ph.D. research. So I helped one of them find fish, and then he won a big tournament. I started getting a lot more requests. I told fishermen that I’d have to hire someone to do the extra work. Then they asked, “How much?” I gave them a number, and they donated money in my name to the university. I eventually left and started my own business. I remain active in academia as I am an Adjunct Professor at the Florida Institute of Technology in Melbourne, FL.

How does ROFFS™ work?

ROFFS™ uses several data sources to view and understand ocean circulation, including satellites, buoys, and ships. This oceanographic information shows us the predictable places where concentrations of baitfish will be. If the conditions stay stable for a few days then fish ranging from sailfish, other billfish, as well as a host of pelagic fish from mahi-mahi to sharks, kingfish, and tarpon find the bait.

Is there always bait in the hot spots that you identify? If so, what makes these predictions so reliable?

We’re looking for convergent zones, areas where deeper water comes toward the surface. When the surface and deeper water meet, the new mixture is heavy and eventually sinks, creating an instantaneous vacuum pulling a variety of particles toward the forming convergence line or frontal zone.

When these convergent zones sit in place a couple of days, algae and zooplankton—small drifting organisms—are drawn into the zone. Within a day or two they attract forage species such as sand eels, squid, sardines, anchovies, and mullet. Day 3 through 10, the bigger fish come in and prey on the forage species.

Help us understand the relationships between water temperature and migrations. As we speak, migrating mullet are pouring down the Indian River Lagoon and out along the beaches. Does temperature play a role in this migration?

Fish have temperature preferences. When they get out of their preferred temperature zones, they get stressed. If the water’s too cold, they have to swim faster and burn more calories. Water that is too warm increases their metabolisms so they also burn more calories and too warm conditions can cause heart and brain damage. For example, generally our experience suggests that mako sharks prefer surface water between 63° and 65 degrees Fahrenheit. Small bluefin tuna prefer 67° to 72°. Yellowfin, 72° to 78°. Blue marlin, 74° to 80°. White marlin, 72° to 79°.

Water temperature is the primary driver of the mullet run. When it gets cold mullet move south. We get migratory mullet in Florida from the Carolinas and Georgia. In an especially cold winter, you get a lot of fish in the Florida Keys. Mullet also come to spawn in huge numbers in Tampa Bay. Wherever you find mullet, they’re food for tarpon, sailfish, and other migratory predators.

Are there specific conditions that influence reproduction among forage fish species? For example, do pilchards like certain ocean conditions that are different from mullet?

Forage fish in most cases are likely to spawn over a relatively narrow range of ocean conditions. Usually the question is whether there’s enough food for offspring to pass through the larval stage to a size where they can escape predators. There are actually a lot of other questions, such as: Is it better for the currents to concentrate or disperse these species? If all the fertilized eggs and larvae wind up in a convergent zone, will basking sharks and squid come along and gobble them all up?

We know that concentrations of larvae can be a good thing for tarpon and shrimp, because storms blow them inshore to settle in our estuaries. On the other hand, there’s definitely a geographic advantage in widely dispersed larvae like tuna and bonefish, because there are better odds that at least some will wind up in favorable nursery areas. We have much to learn yet about larval transport and the mechanisms that favor and hinder reproduction. We are in the final year of a NASA funded project with a variety of other scientists from NOAA, Universities of Miami and South Florida and elsewhere evaluating the effects of environmental variability and climate change on fish larvae distribution.

Besides passing energy up food webs, how else do forage fish contribute to the health of coastal and marine ecosystems?

Forage fish such as menhaden, mullet, and pinfish (for part of their life history) remove substantial amounts of algae from coastal and marine waters. They’re water quality service experts. These and other planktonic eating fish are essential for healthy sea grass beds because they eat algae and dead vegetation that stifle photosynthesis.

You’ve expressed concerns about polluted runoff ruining the Indian River Lagoon (IRL) complex in Florida, one of North America’s most biologically diverse estuaries. How will loss of sea grass habitat and oysters and impaired water quality affect forage fish?

You put all that turbid, polluted water in the estuary and sea grass can’t live. Any organism that forages in the sea grass community, such as pinfish and pigfish, as well as the fish that eat them, just can’t survive because there’s no food.

If you had large enough schools of mullet in the lagoon as well as bivalves such as oysters and clams, they’d help clean up some of the algae in the water since they are filter feeders. But the fish aren’t there. We need to make sure there are enough of them in the IRL complex and in other suffering estuaries so that we don’t—if we haven’t already—go past a tipping point at which the system is lost. If that happens, the grass will take decades to come back—if ever in our lifetime—and would need incredibly expensive remediation.

What, in your mind, should be the restoration priorities for the IRL?

It’s a matter of water and sewage control. We citizens need to make legislators and other decision-makers realize that the IRL is a $2 billion economic engine. We must get rid of the septic tanks. We also need filtration to get rid of excess nitrogen and phosphorous from agricultural and urban runoff. I think the users of the water should clean it before returning it to the ecosystem. I came up with the phrase “Take it, use it, clean it and return it.” All water used inland should be remediated before putting it back into the ecosystem.

What are the implications of declines in forage fish populations for predators such as red drum, snook, sailfish, and various snappers and groupers that spend all or some of their lives in inshore habitats?

These predators need to eat a lot of different species throughout their lives to grow and reproduce. They especially need the calories from forage fish to produce the fat that helps make eggs. Without sufficient forage fish, bad things start happening. Predators through starvation lose weight and start feeding more on each other and especially on each other’s young and on their own young. The fertility and reproductive capacity of these malnourished fish decreases as well. It isn’t possible to maintain predator populations at healthy levels without enough forage fish.

In addition to pollution, what threats do forage fish face worldwide?

Forage fish are threatened by overfishing and loss of habitat. In Florida we’re protecting forage fish through restrictions on certain sized nets, but there are other types of effective commercial gear that are used elsewhere to capture mullet, mojarra, and pinfish, among other species. These include large cast nets and seines. Even with the Florida net ban enforcement of the laws are an issue.

Many forage fish species, including mullet, are staples or delicacies abroad, and increasingly in this country, changing demographics could fuel new and expanded markets for forage fish. We can also expect increasing demands from growing ranks of recreational anglers who need forage for bait.

Then there’s aquaculture. We want healthy fish raised by responsible farmers. But it has to be done in a clean and sustainable manner. It seems foolish to deplete the ocean of wild menhaden in order to feed pen-raised fish. People are using menhaden to feed chickens now. The ocean ecosystem needs these fish to remain healthy.

Habitat loss is also a serious concern. These ecosystem shifts in the estuaries from sea grass to alga are really alarming.

Should we take proactive steps to protect forage fish? What are some examples of how this has been done around the United States?

We need to put a cap on how much fishing of forage species can take place. And then before we allow any increases or permit new fishing efforts to start up on other species, we need to ensure that enough forage fish remain in the ecosystem to fulfill their important role as prey.

The recent report by the Commission on Saltwater Recreational Fisheries Management, A Vision for Managing America’s Saltwater Recreational Fisheries, known informally as the Morris-Deal report, identified forage fish management as a top priority for the recreational fishing community. The commission consists of industry leaders, scientists, and former state and federal wildlife managers. The International Game Fish Association, The Pew Charitable Trusts, the Florida Wildlife Federation, the Guy Harvey Ocean Foundation, and other groups are working together to improve the management of Florida’s forage fish. What actions can anglers take to help these initiatives succeed?

I hope everyone will go online and take the Florida forage fish pledge to encourage the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission to protect forage fish and the habitat they depend on.

For more information on forage fish and what you can do to help protect them in Florida, please visit www.floridaforagefish.org and www.pewtrusts.org/protecttheprey. Of course follow ROFFS™ our home page roffs.com™ from all the social media outlets, and through the ROFFS™ Fishy Times.

Above: Mitchell A. Roffer, Ph.D., an avid offshore and inshore angler shares his kayak with a big common snook that he caught and released alive off the Space Coast in East Central Florida. Snook are endemic only to Florida and southeastern Texas in the United States. This species is one of the most targeted by anglers. Adult snook feed primarily on baitfish, also known as forage fish. Photo courtesy | Mitchell A. Roffer, Ph.D. (President Roffer’s Ocean Fishing Forecasting Service, Inc.)

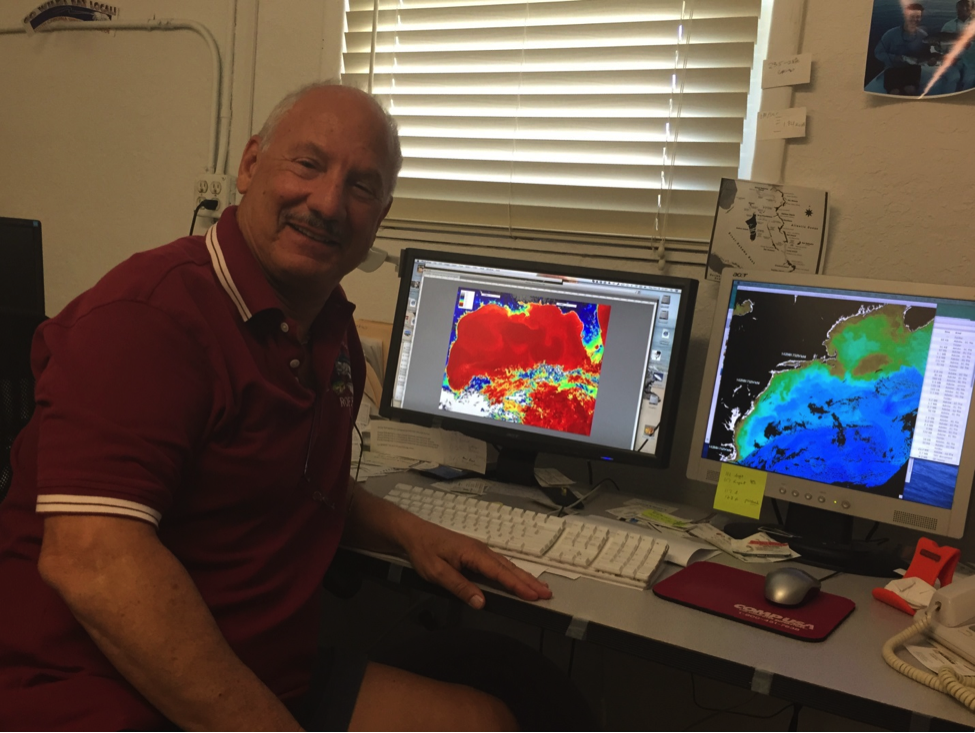

Above: Roffer along with four other fisheries oceanographers at ROFFS™ analyzes oceanographic conditions to identify where concentrations of fish are located. The Adjunct Professor at the Florida Institute of Technology in Melbourne, FL is an expert on how changing oceanographic conditions influence the location and abundance of baitfish and larger predator fish. ROFFS™ also collaborates with researchers and fisheries managers from NASA, NOAA and academic institutions. Photo courtesy | Mitchell A. Roffer, Ph.D. (President Roffer’s Ocean Fishing Forecasting Service, Inc.)

Above: Roffer with a jumbo red drum, also known as a bull redfish, caught in the Indian River Lagoon (IRL) in east Central Florida, before being released alive. The IRL complex—which includes the Banana River Lagoon, several rivers and the Mosquito Lagoon—are popular red drum fishing destinations. Adult red drum rely on forage fish for the energy and nutrients necessary to grow and reproduce. Photo courtesy | Mitchell A. Roffer, Ph.D. (President Roffer’s Ocean Fishing Forecasting Service, Inc.)

*Terry Gibson: Terry Gibson serves as a recreational fishing outreach consultant for The Pew Charitable Trusts in Florida and as senior editor of Fly & Light Tackle Angler magazine. A life-long fly and light tackle angler, Terry has served in a number of field and in-house editorial capacities for highly respected fishing publications, including Saltwater Fly Fishing, Shallow Water Angler, Florida Sportsman and Outdoor life. He also has contributed to leading fishing, hunting, surfing and dive publications since the late 1990s. Terry has fished abroad in ten countries plus the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico, and in more than 40 states. As a multi-lingual journalist covering the issues, or as an advocate working them, he has engaged in conservation issues in more than 20 countries, including the frontlines of water-management, habitat and fisheries management issues in the U.S. Beyond guiding editorial content and feature writing,