Article by Greg Miller | Wired.com – click here for original article.

Above: The Panama canal, shown here, may soon have a Nicaraguan rival. Photo credit: Scott Ableman/Flickr

By the end of this year, if a Chinese entrepreneur gets his way, digging will begin on a waterway that would stretch roughly 180 miles across Nicaragua to unite the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Giant container ships capable of carrying consumer electronics by the millions (or T-shirts by the billions) could begin making the passage by 2019, according to the most optimistic projections.

A canal across Nicaragua has been a dream of kings and entrepreneurs for centuries. Like the ill-fated schemes that preceded it, the newest incarnation has its share of interesting characters, rumors, and controversy. As word of the plan spreads, scientists and other experts are asking questions and finding potentially serious flaws. And they warn that the massive undertaking could become an environmental disaster with dubious financial benefits.

The Nicaraguan government sees the project as a desperately needed economic boost to the country, the poorest in the Western Hemisphere except for Haiti. In June, it awarded exclusive rights to build a canal to a newly created Chinese company, the Hong Kong Nicaragua Development Group. The company is led by Wang Jing, a 41-year old telecom executive. Wang Jing is little-known beyond China, and perhaps even within it, but in an interview with the Financial Times last year he called himself a “very ordinary Chinese citizen” who lives with his mother, younger brother, and daughter in Beijing.

At the same time, Wang Jing’s bio on HKND’s website says he is “board chairman of more than 20 enterprises which operate businesses in 35 countries.” (Right, totally ordinary.)

Above: The proposed canal would pass through Lake Nicaragua. Photo: Zach Klein/Flickr

Under the agreement, HKND would raise the $40 billion needed to build the canal and would have the right to operate and manage it for up to 100 years before turning it over to Nicaragua. In the meantime, Nicaragua would have a controlling interest in the canal and receive income from it.

But there are many lingering questions. How HKND–apparently the only company to submit a bid–managed to land the deal, isn’t clear, leaving many Nicaraguans frustrated by their government’s lack of transparency. “Normally when you have a major infrastructure project you have to place bids, that is the law,” says Jorge Huete-Pérez, a biologist and president of Nicaraguan Academy of Sciences. “Here they overlooked the law and chose this company that has no experience building infrastructure.”

Exactly where the money to build the canal will come from is another mystery, as is the role, if any, the Chinese government will play. Wang Jing has denied that the government is involved in the project, as have government officials. But some analysts suspect otherwise.

The Nicaraguan government sees a huge opportunity in the project. Officials claim the canal will double the national economy, triple employment, and lift more than 400,000 people out of poverty by 2018.

So far the research that led to those numbers has not been made public, says Huete-Pérez. Nor has any assessment of the environmental impacts of the project.

HKND has contracted a global consulting firm, Environmental Resources Management, to conduct an environmental review, which is ongoing. “HKND Group is committed to explore this area with great care and to adhere to international standards of environmental responsibility as it proceeds,” the company says on its website.

But Huete-Pérez and other scientists aren’t content to take the word of a company hired by the company that wants to build the canal. In a commentary published last week in Nature, Huete-Pérez and Axel Meyer, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Konstanz in Germany, argued for an independent review headed by international experts.

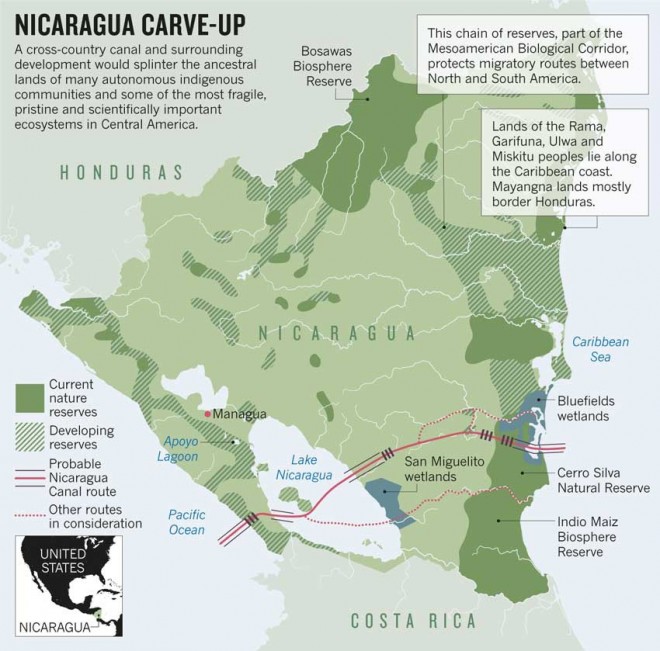

Above: The proposed canal would pass through or near nature reserves and areas inhabited by indigenous groups. Map courtesy of Nature

At Huete-Pérez’s request, Thomas Lovejoy, an eminent conservation biologist at George Mason University, has agreed to lead this effort. “I would like to see a really proper scientific review of what the impacts are likely to be and what the alternatives are,” Lovejoy told WIRED.

The environmental impacts could be considerable.

A final route for the canal has not yet been announced, but the proposed routes pass through Lake Nicaragua, which covers about six times the area of Los Angeles and is Central America’s largest lake.

The lake is a major source of drinking water and irrigation, and home to rare freshwater sharks and other fish of commercial and scientific value, Huete-Pérez and Meyer say. The forest around it is home to howler monkeys, tapirs, jaguars, and countless tropical birds–not to mention several groups of indigenous people (some of whom have challenged the project in court, so far to no avail).

Meyer, who’s done field work in Nicaragua for 30 years, says the area is a natural laboratory for evolutionary biology. Just as Darwin’s finches evolved into different species as they adapted to the unique environment of individual islands, so it goes with fish as they’ve colonized the region’s network of crater lakes. “These crater lakes are like islands in a sea of land from a fish’s perspective,” said Meyer, who has been characterizing genetic changes in the region’s cichlid fish populations.

Exactly what ill effects would result from the canal aren’t clear, partly because the plan itself is not clear. But here are a few scenarios.

Huete-Pérez and Meyer worry primarily about the dredging necessary to accommodate massive container ships: The proposed canal is 90 feet deep; the lake averages just 50 feet. “The initial digging would create a huge sediment issue that would be bad for water quality in the lake and the wetlands around it,” Meyer said.

Pedro Alvarez, a civil and environmental engineer at Rice University raises another water-related concern. It may be necessary to dam the San Juan River, the main route for water flowing out of the lake, to keep the water levels high enough for the canal’s locks to work properly, Alvarez says. “If you do that you’re going to change the hydrology of many lakes and rivers,” he said. “Some may dry up.”

Lovejoy sees other potential problems. He’s especially worried about creating a conduit between the Pacific Ocean and Caribbean Sea. “It’s creating the potential for an enormous invasive species problem,” he said. That problem could include venomous Pacific sea snakes invading the Caribbean and a disruption of Caribbean fisheries from an influx of competing species, predators and disease.

Above: Lake Nicaragua. Photo: Axel Meyer

That hasn’t happened in Panama because the canal route there is entirely freshwater, presenting a formidable barrier for marine life. But in Nicaragua, the topography that separates the Pacific and Caribbean is lower, permitting a canal route that’s closer to sea level and potentially filled with saltwater for more of its length (this will depend on the details of the design, which have yet to be disclosed).

Huete-Pérez points out another possible impact on marine life: The canal could create a major shipping route in close proximity to Seaflower Marine Protected Area a UNESCO World Heritage site off Nicaragua’s Caribbean coast. This area encompasses one of the largest coral reefs in the Americas and is home to scores of endangered marine species. An oil leak or other accident in the region could be disastrous.

All the same, Meyer says he understands the need to balance economic and environmental factors. While he’d rather see Nicaragua follow the lead of Costa Rica and develop an ecotourism economy instead of the canal, he realizes there’s a touch of hypocrisy in outsiders from industrialized countries preaching environmental purity. “How can I as a gringo from Germany tell the Nicaraguans what to do? It’s hard to tell them not to make the same mistake we made centuries ago.”

But even the economic benefits aren’t guaranteed. The Panama canal celebrates its 100th birthday this year, and it’s nearing the end of a $5.25 billion expansion project. When the new and improved canal opens early next year, it will allow ships with three times the cargo capacity to pass through, and it will handle up to 16,000 ships a year, roughly a 15 to 20 percent increase, says Jean-Paul Rodrigue, an expert on transportation economics at Hofstra University. “It’s going to take a while for this capacity to be absorbed, if it ever is,” Rodrigue says. “In the medium term, there will not be a need for another canal.”

Proponents of the Nicaragua canal have pointed out that even the new canal in Panama won’t accommodate the latest generation of mega container ships, the so-called Triple E class, which can carry up to a third more cargo. But Rodrigue notes that few ports in the United States, Caribbean islands, or Latin America are equipped to handle these massive ships. Some ports may be overhauled to accommodate these massive ships by the time a canal could be built in Nicaragua, and a few ports in the U.S. have already gotten started on this, but it’s not clear how many will follow suit.

There’s also no geographic advantage to a canal in Nicaragua, Rodrigue says. The few hundred miles shaved off major shipping routes between Asia and North America would be balanced out by longer transit times through a canal that’s more than three times as long as its competitor in Panama.

All in all, Rodrigue says, “At this point in time, from a commercial standpoint, this project does not make sense.”

This isn’t the first time a canal through Nicaragua has been proposed — far from it. The Spanish looked into it in the 1500s. Napoleon III took up the cause three centuries later. And in the early 1900s, the Americans almost did it. Advocates of a Nicaragua canal argued for its advantages over the competing route in Panama, including the lowest passage anywhere between Alaska and Tierra del Fuego, a seemingly endless supply of freshwater, surrounded by fertile land that was relatively free of disease (in Panama, malaria and other tropical diseases contributed to a horrific death toll: at least 25,000 workers died during the canal’s construction). In the spring of 1902, the plan seemed assured of approval by Congress.

But it all came undone with a postage stamp, or so the story goes. Proponents of the Panama route had been making a big deal of Nicaragua’s menacing volcanoes and earthquake prone ground. French engineer Philippe-Jean Bunau-Varilla seized upon the fact that the Nicaraguans featured an erupting volcano on their own postage stamps. Shortly before the U.S. Senate was to vote on the canal plan, Bunau-Varilla managed to round up 90 copies of the stamp and sent one to every Senator. In a narrow vote, the Panama route was approved.

The seismic risks may have been overblown for political purposes. But they’re not negligible, and they probably represent the worst-case scenario, says Alvarez, the engineer from Rice University. “Releasing a dam could be a catastrophic event that I don’t even want to think about,” he said.

He’s more concerned about less dramatic but higher probability risks, like the slow degradation of the environment, or — even more likely in his view — the prospect of work getting underway on the canal only to be abandoned when the going gets tough or the money runs out.

“I’m not very hopeful to be honest,” said Alvarez, who was born in Nicaragua and is a member of its academy of sciences. He says the issue has personal meaning for him.

“This hits a very deep nerve in me,” he said. “I grew up swimming and fishing in this lake. I would like my grandchildren to experience some of that.”