A bright new chapter for bluefin tuna has begun. NOAA Fisheries just issued a strong final amendment Aug. 29 for protecting these giants of the ocean. With the promulgation of implementing regulations, the new amendment will help stop western Atlantic bluefin—and approximately 80 other types of marine wildlife—from unnecessarily dying on surface longlines, fishing gear that is intended primarily for yellowfin tuna and swordfish, but indiscriminately kills other species.

“NOAA Fisheries deserves great praise for significantly increasing protections for bluefin while allowing fishing for yellowfin tuna and swordfish to continue,” said Lee Crockett, director of U.S. ocean conservation for The Pew Charitable Trusts. “This historic action will help western Atlantic bluefin tuna rebuild to healthy levels.”

Bluefin tuna command respect. They’re as fast as racehorses, bring fishermen to their knees, and grow to the size of a small car. These “superfish” make transoceanic migrations, can dive deeper than 4,000 feet, and live up to 40 years. But bluefin are no match for wasteful fishing methods. The population of western Atlantic bluefin tuna is just 36 percent of its already depleted 1970 level. This decline is caused in part by surface longlining.

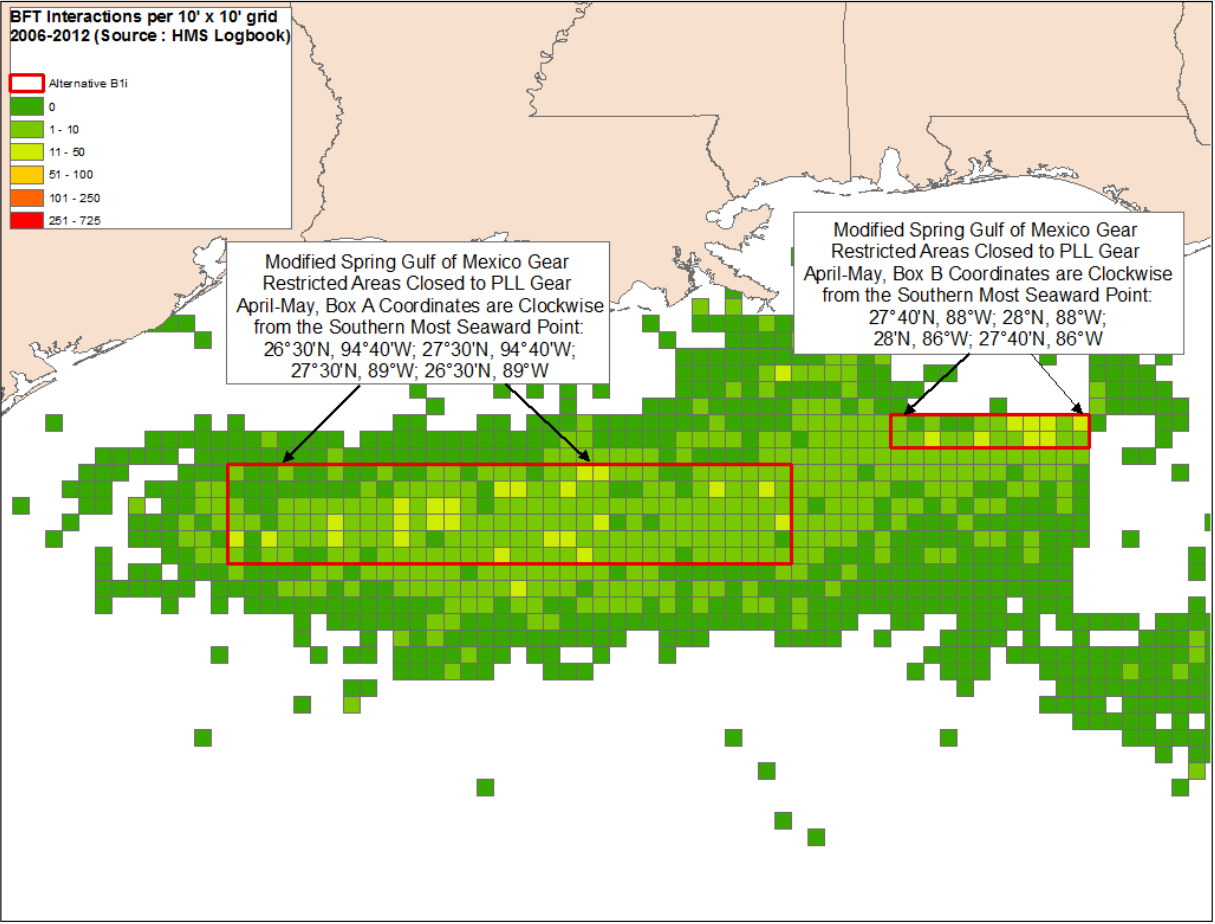

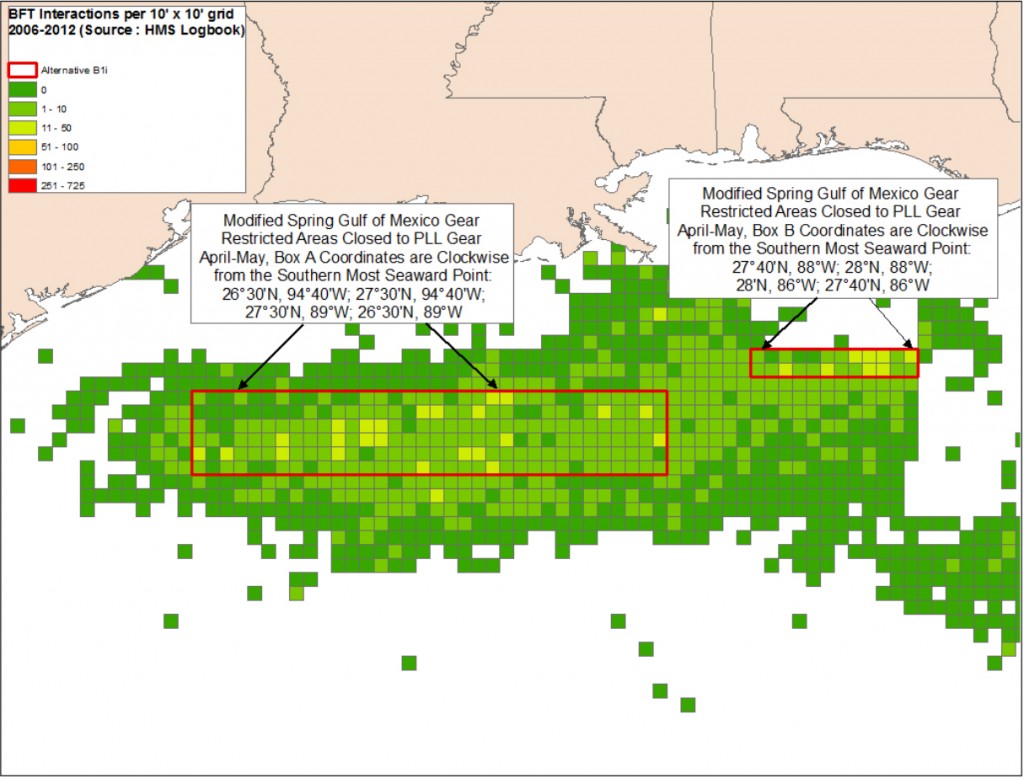

Modified Spring Gulf of Mexico Gear Restricted Areas (Photo Above.)

Surface longlines average 30 miles in length, use hundreds of baited hooks, and often remain in the water untended for up to 18 hours. This gear catches and kills bluefin along with many other species, including hammerhead sharks, blue marlin, and leatherback sea turtles.

For the past half-century, surface longlines in the Gulf of Mexico have been a serious danger to western Atlantic bluefin tuna. The Gulf is the fish’s only known spawning area. The same fishing gear poses a similar threat to bluefin feeding off the coast of North Carolina.

NOAA Fisheries has tried for decades to reduce the incidental catch, or bycatch, caused by surface longlines. Fishermen have been prohibited from directly targeting bluefin tuna in the Gulf since 1982. The agency also required gear modifications and bait restrictions. None of those options has provided the comprehensive solution this problem demanded.

The agency realized it needed a different approach. It spent five years developing new management measures to help protect bluefin tuna while also supporting fishermen who use highly targeted methods.

Today’s final amendment restricts the use of surface longline fishing in certain areas of the Gulf of Mexico and off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, while promoting highly selective gear such as greensticks for yellowfin tuna and buoy gear for swordfish. Ensuring that surface longlines are not used when and where bluefin gather in great numbers to spawn and feed will dramatically reduce the amount needlessly caught and killed.

This amendment also establishes a new annual limit on the incidental catch of bluefin on surface longlines and 100 percent electronic monitoring of the surface longline fleet. Thanks to these and other changes, the agency will now be able to hold individual surface longline vessels accountable for their incidental bluefin catch. NOAA Fisheries will also be able to prevent the fishery from exceeding its total allowable bluefin catch. This limit is needed: Surface longlines catch more bluefin tuna now than before 1982. In 2012 alone, surface longline vessels in the Gulf and western Atlantic Ocean discarded 445,338 pounds of dead bluefin tuna. This quantity was more than 20 percent of the entire U.S. bluefin quota for that year.

“The two new gear-restricted areas in the Gulf are a tremendous achievement,” said Crockett. “For more than 10 years, scientists, fishermen, and other stakeholders have urged the agency to protect western Atlantic bluefin in their only known spawning area. NOAA Fisheries clearly demonstrated its dedication and commitment to restoring bluefin tuna.”

One disappointing aspect of the amendment, however, is the reallocation of bluefin tuna quota away from selective fishermen using rod and reels and harpoons to the surface longline fleet. Providing more bluefin to the surface longline fleet does not promote conservation of the species and reduces fishing opportunities for traditional bluefin fishermen.

“Despite this reallocation, this final amendment is stronger than the draft and will help put depleted bluefin tuna on the road to recovery,” said Crockett.

Re-posted from pewtrusts.org – please click HERE for the original article.