A technological revolution is needed for Europe to end the controversial practice of discarding fish, according to the EU’s fisheries commissioner.

Maria Damanaki is calling for boats to be fitted with smart nets to filter out fish which would later be discarded as too small or above quota.

And she wants more on-board cameras to ensure that crews cannot cheat on fishing rules.

She told BBC News that the hoped-for reform of the Common Fisheries Policy could not happen unless fishermen harnessed new technology.

Spy-in-the-wheelhouse CCTV cameras trialled in the UK are said to have cut cod discards from 38% to just 0.2%.

Fishermen on the trial are obliged to land all the cod they catch, whatever the size. They have been rewarded with increased quotas and permitted extra days at sea.

Ms Damanaki says cameras will be essential – especially for the biggest boats – if the EU adopts a policy of zero fish discards.

Smart nets

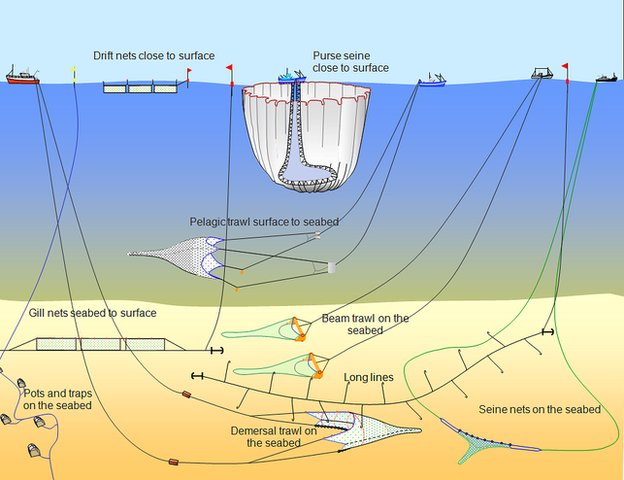

The other key technology is fishing net design, which Ms Damanaki says is the single most important component of fisheries reform.

At the North Sea Centre in the Danish port of Hirtshals, fishery technologists are testing new styles of nets which may answer her prayer.

Fishing crews travel here to learn about smart nets which separate catches by new designs.

One innovation is a slanting plastic grid at the centre of a trawl net. Large fish are diverted by the grid into the keep end of the net whilst young fish and shrimps pass through the slots. The grid is bendable so it can be wound up with fishing gear.

The bendy grid costs around £2,000 – a sum which prompted British fishermen visiting Hirtshals to laugh out loud.

But Mrs Damanaki told me she hopes to subsidise the cost of new technology for small boats by 85%. The bendy grid may prove the difference between being allowed to fish and being kept out of the water.

The Rollerball net is another recent arrival. Traditional beam trawlers seeking flatfish drag heavy gear along the sea bed, churning up the sand and destroying much that lies in their path.

Rollerball runs over the seabed on what look like beach-balls. It is said to reduce damage and drag by between 11 and 16%, and there are hopes for further improvements. Cutting drag also trims fuel bills and pollution.

Embracing change

Mike Montgomerie from the UK quango Seafish introduces crews to the latest technologies at Hirtshals. He said: “In the past few years I have noticed a real change among crews. They are hearing that the public won’t put up with wasteful fishing any more, and a lot of them are embracing change.”

Ms Damanaki went further: “The most important (thing is) how we are going to implement selective gear so we can reduce unwanted catches. This is the most important element of the whole policy.”

The crews I met appeared to be accepting change rather than actually embracing it.

In Scarborough, Yorkshire, boat owner Fred Normandale said he resented the trial cameras on his trawler Emulator, but the trial made financial sense: “It feels like we are being spied on – I wouldn’t want the cameras to be mandatory,” he said. “I have only done it because they paid for it and made it worth my while in quotas and extra days at sea.”

His skipper, Sean Crowe, told me the spy cameras have changed the way he operates. “It makes you think more about where you are fishing. In the past if we brought up a lot of young fish we might have another haul to see what would happen. Now we move somewhere else and we check with other boats to see what they are bringing up.”

The on-board spy is a sophisticated system employing cameras; GPS; and infra-red and hydraulic sensors to monitor the winches. It produces a map of exactly where the boat has fished in the last two months, as well as evidence of what it has caught.

The kit costs £7,000, installation adds £2,000 and software puts on a further £300 a year.

Vested interests?

But the Marine Management Organisation (MMO), which is running the trial, says this is still cheaper than human observers on boats – and much more effective, as the computer hard-drives hold far more information.

“A fisheries observer on a boat has one pair of eyes,” says Grant Course, head of the marine trials team. “With the cameras we can watch four areas of the boat at the same time, including the discards chute. We can see the fish being sorted. We really know what’s going on.”

The wheelhouse spy has been used for a decade in North America’s successful attempt to restore fisheries, but it may be resisted by some European governments.

The new net technologies are also effective, but the highly individual local conditions of fisheries may confound the sort of blanket technological rules that appeal to Brussels for ease of enforcement. A net that protects the environment in one fishery may not work well in another.

It will be hard for politicians to sort genuine complaints about inappropriate gear from the vested interest that has driven Europe’s fish stocks to their current depleted level.

Commission sources fear that France and Spain may accept the principle of a discards ban but raise sufficient technical objections over gear rules to render reform ineffective.

That, insists Ms Damanaki, must not be allowed to happen. But it is a sign of the changing times that the EU is no longer talking about whether fishing reform is necessary, but how it is achieved.